Why it only costs $10k to ‘own’ a Chick-fil-A franchise

Posted on Jan 21, 2020

THE HUSTLE, BY ZACHARY CROCKETT – JANUARY 19, 2020The chicken chain is known for having the lowest entry cost of any major fast-food franchise — but there’s a catch.

In America, the majority of fast-food restaurants aren’t owned by the corporation itself, but by franchisees — individuals who pay for the right to use a brand name.

Instead of buying and developing new properties with their own money, most national chains (franchisors) will allow a party or individual (franchisee) to front the development bill and take a stab at ownership in exchange for a cut of the sales.

Many people dream of buying a fast-food franchise of their own, but few can afford it.

All told, it might cost a franchisee upwards of $2m to develop, build, and buy the right to open a McDonald’s or a KFC. Many chains won’t even look at your application unless you have a net worth of $1m and $500k in readily spendable cash sitting around.

But there’s an exception to this: A franchise at Chick-fil-A — one of America’s oldest, largest, and most profitable chains — can be yours for just $10k.

Before we get into how this is even remotely possible, let’s first take a step back and look at the economics of a traditional fast-food franchise deal.

How much does it cost to buy a fast-food franchise?

To better understand the capital required to acquire and launch a fast-food franchise, The Hustle spoke with more than a dozen franchise owners and analyzed data from franchise disclosure documents filed by 22 of the largest domestic chains.

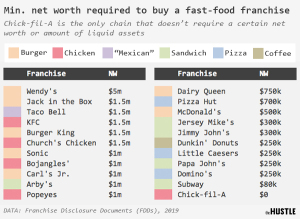

For starters, it’s a feat just to qualify to buy a fast-food franchise from one of the big players — a franchisee has to be prettttttt-y pretttttt-y wealthy.

The average chain we looked at requires an applicant to have a minimum net worth of $1m ($500k of which is liquid). Burger chains and chicken chains appear to have the highest barrier to entry: To launch a Wendy’s, you need to have at least $5m in the bank, with $2m in liquid assets.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

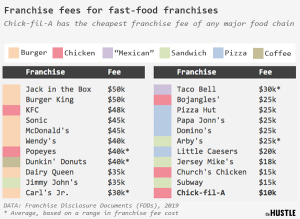

If you’re fortunate enough to get accepted, the first thing you’ll do is dish out a franchise fee — an upfront, one-time payment for the right to enter into business with the chain.

At an average of ~$30k, franchise fees make up only a small part of a franchisee’s total investment. The rights to big burger chains like Jack in the Box and Burger King will set you back $50k; sandwich chains like Subway can be had for $15k.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

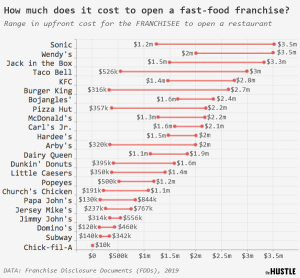

The bulk of the cost, though, lies in the development of the store: Real estate, building fees, equipment, inventory, and everything else necessary to get a new restaurant off the ground.

“The [chain] doesn’t want any liability with financing or developing,” says Reas Kondraschow, who owns 9 Five Guys in Broward County, Florida. “When it comes time to build, the franchisor is generally pretty hands-off.”

It’s the franchisee’s responsibility to cover all of these costs prior to opening.

This figure, called the total initial investment, varies widely based on the type of storefront (mall, drive-thru, dine-in) and the location. A McDonald’s in a small Southern town might cost 50% less than one in a major city.

For this reason, the estimated cost of a franchise is listed as a range in franchise disclosure reports. The chart below visualizes the lowest and highest range of what a given franchise might cost. (We ranked the results by the highest estimate.)

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Overall, the average fast-food franchise costs between $777k and $1.9m to open. Though, according to the franchisees we spoke with, it’s realistic to expect to be on the higher end of this.

Shareef Aminmadani, whose family runs 64 Taco Bell franchises in Tennessee and Kentucky, tells The Hustle that his initial investment usually breaks down like so:

- Franchise fee: $45k

- Building: $900k

- Equipment: $380k

- Real estate: $250k to $1m

Like other franchisees we spoke with, Aminmadani pays ~25% of this amount ($400k-$575k) in cash, then uses loans and/or investors to cover the rest.

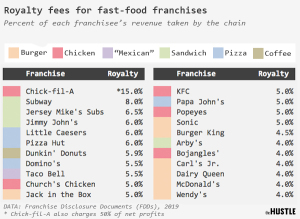

And what does a chain get out of letting someone else build and own a property under its brand name? Aside from the franchise fee mentioned above, it generally takes a royalty fee of anywhere from 4-8% of the store’s monthly sales. For his Taco Bells, Aminmadani pays 5.5%.

In addition to this royalty fee, a franchisee also pays another 2-6% for advertising (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

When properly leveraged, this model is a win-win for both parties: The chain can expand quickly and pass off the financial liability of owning and operating a store; the franchisee gets to own a business with a pre-established brand and a built-in customer base.

But at Chick-fil-A, things are done a bit differently.

Why Chick-fil-A franchises are so cheap

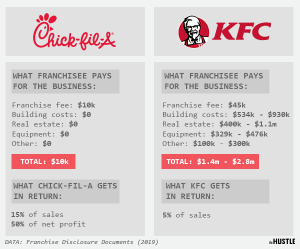

Take another look at the charts above, and you’ll see that Chick-fil-A stands out in a few ways:

- It has no minimum net worth requirement.

- It has the lowest franchise fee of any chain ($10k).

- It has (by far) the lowest total investment cost for a franchisee ($10k).

- It charges (by far) the highest royalty fee.

Chick-fil-A pays for (and retains ownership of) everything — real estate, equipment, inventory — and in return, it takes a MUCH bigger piece of the pie.

While a franchise like KFC takes 5% of sales, Chick-fil-A commands 15% of sales + 50% of any profit.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

This model makes sense for Chick-fil-A for a few reasons.

At $4.2m per store, Chick-fil-A’s average revenue is the highest of any fast-food chain in America, dwarfing both direct competitors (KFC; $1.2m) and bigger brands (McDonald’s; $2.8m). That’s especially impressive considering that all Chick-fil-A restaurants are closed on Sunday.

Based on these figures, Chick-fil-A’s 15% royalty alone (not including its 50% cut of profits) might work out to around $600k per store, per year. (And remember: It still owns the property and equipment.)

This set-up can also work out to be a pretty sweet deal for Chick-fil-A’s franchisees. That is, if you can land the job.

A lower acceptance rate than Stanford

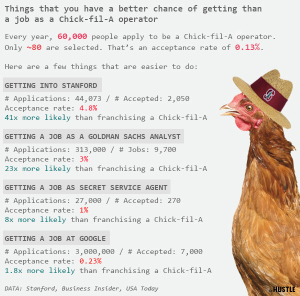

According to Chick-fil-A, 60k people apply to be operators every year — and only ~80 are selected.

With a 0.13% acceptance rate, it’s harder to become a Chick-fil-A franchisee than it is to get into Stanford University (4.8%), get a job at Google (0.23%), or even become a special agent for the Secret Service (1%).

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Chick-fil-A Operators go through a screening process that often lasts months.

Quincy L.A. Springs IV, a Chick-fil-A Operator in Atlanta, had to complete 10 rounds of interviews, write 12 essays, and provide a copy of his high-school transcript. Once selected, he went through an “extensive, multi-week training program” covering everything from menu education to employment law.

In lieu of wealthy investors, Chick-fil-A selects franchisees who are involved in their local communities. The company’s aim, says a spokesperson, is to find people who are willing to be “highly involved” in day-to-day operations. (While not a stated requirement, adhering to “Christian values” also doesn’t hurt an applicant’s chances).

“You run every aspect of the restaurant six days a week,” says Jeremiah Cillpam, a Chick-fil-A franchise owner in Los Angeles. In return for 60-hour work-weeks, an operator might take home 5-7% of revenue (around $150-$250k per year).

But from an investment perspective, certain things about being a Chick-fil-A franchisee aren’t so enticing:

- They don’t own the restaurant or equipment (everything belongs to corporate).

- They don’t have any equity stake in the business.

- In most cases, they aren’t permitted to “own” multiple locations.

- They aren’t permitted to run any other business.

“When people start a business, they want flexibility and real ownership,” says Kenny Rose, CEO of Semfia, a firm that educates people on franchise investing. “But as a Chick-fil-A franchisee, you’re basically just working a traditional management job.”

“A war for pennies”

Outside of FDD forms, financials on fast-food franchises are shrouded in mystery. Under FTC regulations, franchisors aren’t permitted to throw around earnings claims and franchisees are often hesitant to share their profit margins and ROI.

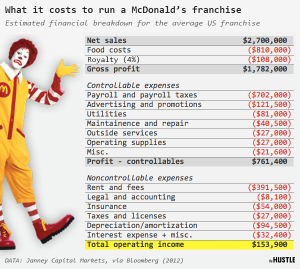

According to the annual reports of publically-traded fast-food chains, margins for franchised restaurants are usually razor-thin, ranging from less than 1% (Pizza Hut) up to 13% (KFC).

This can be especially true at enormous chains like McDonald’s, where overhead can eat into profits faster than the Hamburglar.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Those who own multiple franchises — or an empire of them — can make millions. But research published by Franchise Business Review found that 51% of food franchisees earn less than $50k per year and only around 7% take in $250k.

“As a fast-food franchise owner, you’re often fighting a war for pennies,” says Rose. “Food is the most competitive industry known to man: It has the highest investment level of any industry, the highest failure rate, and the lowest margins.”

At Chick-fil-A, some of these risks are mitigated by a low initial investment, booming sales, and good margins — but this comes at the expense of true ownership.

Follow Us!